GOING FORWARD

Survivor

Through the tears

I make the most

of all I have

and seek more.

Building a New Life

Time and space are the gifts

they give us,

our deceased partners.

New.

Unwelcome.

Baggage attached.

What to do with them?

Never Safe

Wham, bam, here it comes again,

sudden tears, deep sadness,

sitting in the opticians,

trying on my new specs,

peering at the new me

through bleary tear-filled eyes.

I look different from how he saw me.

Such a seemingly safe activity

on an ordinary Friday morning.

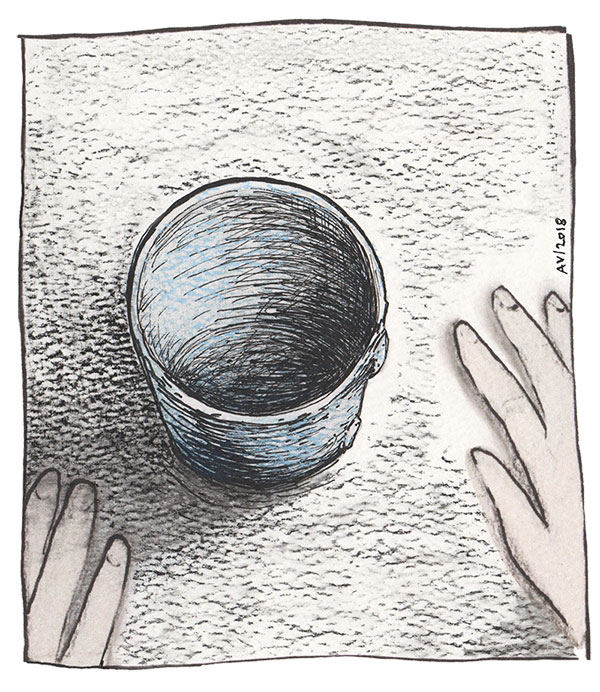

Digesting Life

We lived life twice,

double the value.

Cow-like, in our together time

as we cooked, sat over a meal,

we would bring back up

stories of our day,

chatting over events, sights, experiences,

extracting every last drop

of interest, learning,

humour, sadness.

So was I nourished.

Alone, after your death,

I have worked very hard

at the art of solo digestion.

Am rounding out and sleek

once more.

Another Milestone

I took it off today,

two years after you died.

I’d tried before

but it hadn’t felt right.

Over thirty years I wore it, always.

Our marriage now a memory.

No widow’s weeds, a ring.

It’s sitting on the chest of drawers.

His Clothes

For months our bedroom looked the same.

A visitor would not know he wasn’t there.

Clothes hanging, drawers full, books by the bed.

Only the rounded pillow, plumped up by me after you died,

showed your absence.

(You were not one to straighten your bed in the morning.

But only I would notice that).

Clothes in the laundry bag got washed and replaced.

What else to do? Every so often I opened a drawer,

touched the row of trousers and shirts,

then turned away. daunted, decisions beyond me.

Not yet then.

Finally, one brave day, tears running down my cheeks,

I took big plastic bags and carefully filled them,

sorting as I went, socks in one, shirts in another, trousers, fleeces.

A few precious, favourite items saved in one special “you” drawer.

A couple of jumpers put into mine, for wearing in those hard moments,

when I needed to feel your strength.

Into the loft they all went. Gone.

After the funeral, your son had already taken

your heavy, dark green dressing gown off the back of the door.

Our bedroom, my bedroom, looked

suddenly naked, starkly empty,

crying out to be filled.

I found more hangers, stretched my clothes along the rail,

spread my things among the empty drawers.

All in a semblance of solo ownership, an act initially,

till I could do it for real,

inhabiting the space as mine alone.

It was many months till I knew what to do next,

the bags sometimes weighing on me,

up there, very close, in the loft.

Options running round in my head, unresolved,

till I decided on a simple process,

a big relief to know and put in motion.

After Christmas, for your son’s birthday,

we all gathered here, four children and their families,

an occasion to remember and celebrate, the first time since the funeral.

We scattered your ashes on the allotment,

shared your favourite Sunday cooked breakfast.

Alone each adult went into the loft, chose a few items.

Not easy.

Later, much later,

I invited your three closest friends

to choose and take what they wanted.

Friends well versed in second-hand clothes,

charity-shoppers all, as you were,

appreciating an opportunity to expand their wardrobes,

wanting to own and wear a memento of you,

helping me out with a difficult task.

Waiting, nervous, tearful, afraid.

I needn’t have worried – it was wonderful,

a big celebration of you and life.

You would have loved it.

All the bags laid out on my daughter’s double bed.

In we all dived, a glorious jumble sale,

but with mirrors, and trying on, no price tags, experimenting,

with friends to comment and admire.

We delighted in memories of you.

I remembered where things came from.

They talked of occasions they had seen you wearing that shirt,

that jacket, those stylish, stripey socks.

”Step up, step up” we shouted in unison,

as they dared to be smarter in your classy work outfits.

Or “That’s you”,

as another sported your favourite tweed cap

and your black, charity-shop, funeral coat.

Prize items, your pink tee shirts, some of your lovely shirts,

(you had an eye for quality cloth and design),

were negotiated over.

Pleasingly, even your trousers fitted and were chosen,

all three slender men, near enough your height.

The biggest transformation was in Adrian,

usual wearer of baggy jogging bottoms, worn old tee shirts, hoodies.

Your well-cut, hardly worn black suit fitted him a treat.

With a smart shirt underneath, he looked a different man.

We applauded his beauty.

At last, with talk of having a smart dress-up party

to show off their new looks,

they left in triumph, a job well done.

Much was left of course, ties, braces.

Days later they too were bagged up and taken to the village charity shop,

with a request for display off my patch, elsewhere.

(I did not want surprises. Seeing the three of them was fine,

sporting familiar clothes, but not strangers).

And now sometimes there is a soft hollow in the pillow next to mine.

Left by Adrian who,

though wearing your shirt before,

does not wear your clothes

as he slips into bed beside me.

But that was much later.

And you would have liked that too.

His Shed

Nearly two years now

and I still haven’t tackled clearing his shed,

his beloved timber-framed workspace,

beautifully designed and built,

his desk for architectural drawings looking out over the garden,

my mother’s comfy old armchair in front of the wood-burner.

Books and tape-recorder to hand on shelves beside,

plenty of room for motor-bike mags.

His British vintage motor-bikes just feet away, in the workshop,

a simple slipping through the skinny interconnecting door.

(He always did want to live in a shed at the bottom of the garden).

Gradually I have moved his possessions

from the house into his shed,

pictures no longer wanted,

books, music, instruments,

until the house feels fully mine for me alone.

He is there, of course,

in every saucepan, every wooden spoon,

the windows he carefully designed,

the coffee pot, the piano, the self-closing loo seat,

yes everywhere,

but I can live with that. It’s now my norm.

The shed feels different,

his own space, where I was a visitor, not a co-habitee.

Long desk still covered with papers he was working on,

pencils, pens, next project drawings, a list of materials.

Low shelf, now dusty,

holds the book he was reading, notes he was making.

Once I go in and make order,

tidy up, remove, dispose of,

he will be truly gone.

A naked space.

The stripped bed after a hospital death.

No, not yet, not yet.

Soon.

Clearing Your Work-table

Today I started. Not easy.

How could it be after two years?

Special pens, pencils, slide-rule, set square,

precious tools of your architectural trade,

littered over and around your drawing board, left in mid-flow.

Small motor-bike bits, a pile of well-thumbed business cards,

carefully sought over many years and many events,

skilled enthusiasts, creating replacement bits,

fine tuning, out of distant sheds and garages.

The list for your favourite hardware shop,

the small bag of specified screws,

ready for your next garden structure project.

All now just detritus, not needed on your journey.

I move slowly, gently, not knowing how to do this,

such an intrusion into your space, your things.

Start simple.

With my duster I begin to tidy up,

cleaning each item in turn,

seeing them in your beautiful hands. Sorting, grouping.

Separate piles, dead wasps and spiders into the bin.

OK. Keep breathing.

Next I realise I could move it all to the door end,

wipe the whole surface,

stack neatly at the window end.

Yes, that works.

Soon I have neatness and order.

The beauty of quiet emptiness.

Summer Separation

In late August he loaded his elderly BMW

with tent, stove, food, walking boots,

heading for the Isle of Man ferry,

his annual pilgrimage to the Manx, the classic bike races.

In his luggage, near to hand, a large Tassajara cake

baked by me, to the monks’ special recipe,

varying a bit every year,

sometimes dark with blackcurrants, often crimson with raspberries,

always brazil nuts, coconut, raisins, oats.

His ritual sustenance for the tiring journey and the settling.

Back home for twelve days alone I continued the looking after,

house, garden. A few texts or phone calls, hearing the quiet.

The October after he died I took his ashes across the sea,

to scatter on the course, at his favourite camping spot,

away in the field, under the oak tree.

Feeling his love for the island.

These days it is I who enjoy beautiful home-baked cake and bread,

dense with fruit and nuts, brought to me by my new man,

to feed and sustain me in my solitary life here at home.

But I still miss the missing.

Revisiting Pembrokeshire

He will be with me

as he always was

as I stride along the coast path,

rest my back against a rock

with picnic and vast sea-views,

feel the waves soft over my feet

He will be with me

as he always was

at the lighthouse,

round the harbour,

in the cathedral

This time

no-one else will see him.

The House is Mine

I have been knocked through,

one long room now,

new stove and hearth,

wooden floors, walls painted,

soft wool, nice shade.

Confidently and kindly

the experts swept away

the spaces we had shared.

After they left,

I cleaned the windows,

the first time.

(He liked cleaning windows,

but that was a long time ago).

Carefully rubbing

the big panes

and the little lights above,

I wiped away

the last remains of his breath.

First Tellings

My mother got two from me,

those can’t wait to tell her,

daughter to mother imperative phone calls,

fresh from the joyful life-changing event.

“I have met him, he is the one”.

Two and a half years later,

seven a.m., I nipped next door in

my dressing gown, my phoneline down,

leaving my newly home-birthed baby with him,

now my partner, the new dad.

“I have had a daughter”.

Much later I had moved into the mother slot,

this first baby daughter an adult.

I was at work for my first receiving,

discussing wording for important documents,

my mind more focused on a Manchester hospital.

“You have a granddaughter”.

I rang her dad at once, drove home,

celebrated with him,

our new grandparenting lives stretching before us.

We were together for the next, our younger daughter.

In a Coventry hotel, Sunday breakfast,

cathedral yesterday, transport museum today.

The place was packed with coach parties.

“We are an item”.

That time he congratulated too over the phone.

We beamed all day among the ancient vehicles.

This last one I was in front of the wood-burner,

Monday evening, reading, alone.

My younger daughter at Macbeth at the National Theatre,

her thirty-first birthday outing from her live-in partner.

She phoned in the interval.

(Not a big birthday, that was last year).

“We are engaged.

You are the first to know”.

(His parents next, then her sister).

“Don’t tell anyone”.

But he is not here to tell, your dad.

Who else matters?

I hope there will be more receivings.

I will withstand the pain.

Still Processing

Back from the hospice,

our house full, we paused,

felt the gap,

planned what next.

They dispersed,

my daughter and babies

staying to help.

All here again for the funeral,

a big celebration.

Then I was alone.

Five years on, memories continue to press.

Time Does Help

To start with I stumbled a lot,

tripping up endlessly over the missing of you.

Sudden, sharp shocks of hurt,

upsetting my attempts to move forward.

Now the way feels clearer.

I am getting into my stride,

gliding more smoothly over the humps of sadness.

I have been stretched.

0 Comments